Strategy for Micro-frontends

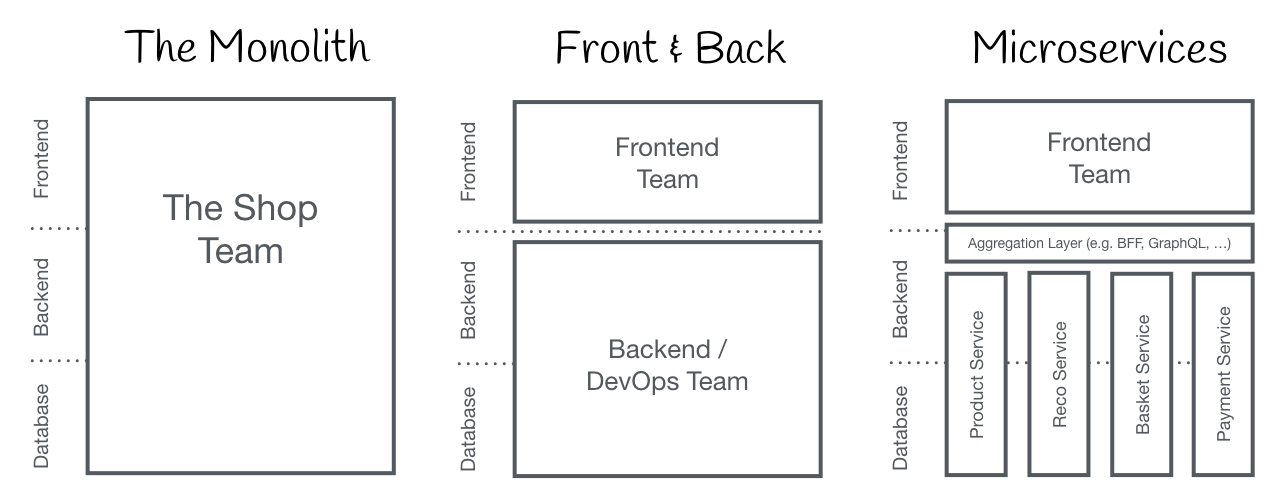

Recently, we’ve seen an increase in the emphasis placed on the overall architecture and organizational structures required for complex, modern web development. Patterns for decomposing frontend monoliths into smaller, simpler chunks that can be developed, tested, and deployed independently while still appearing to customers as a single cohesive product are emerging. Thus emergence of Micro-Frontend’s:

Micro-frontend architecture is a design approach in which a front-end app is divided into individual, semi-independent “microapps” that collaborate loosely. The micro-frontend concept was inspired by and named after microservices.

Pros and Cons

Pros:

- Iterative, Agile development

- Team Autonomy

- Deployment independence

- Bounded context inline with microservice

- Definitive team ownership/accountability

- Use of purpose fit frameworks(Framework freedom)

- Better individualized testing and manageability

- Reusability

Cons:

- Duplication of dependencies

- Increased payloads effecting performance

- Potential Fragmentation of standards

- Complex initial set up and deployment process(until it is streamlined)

- Complex integrated testing

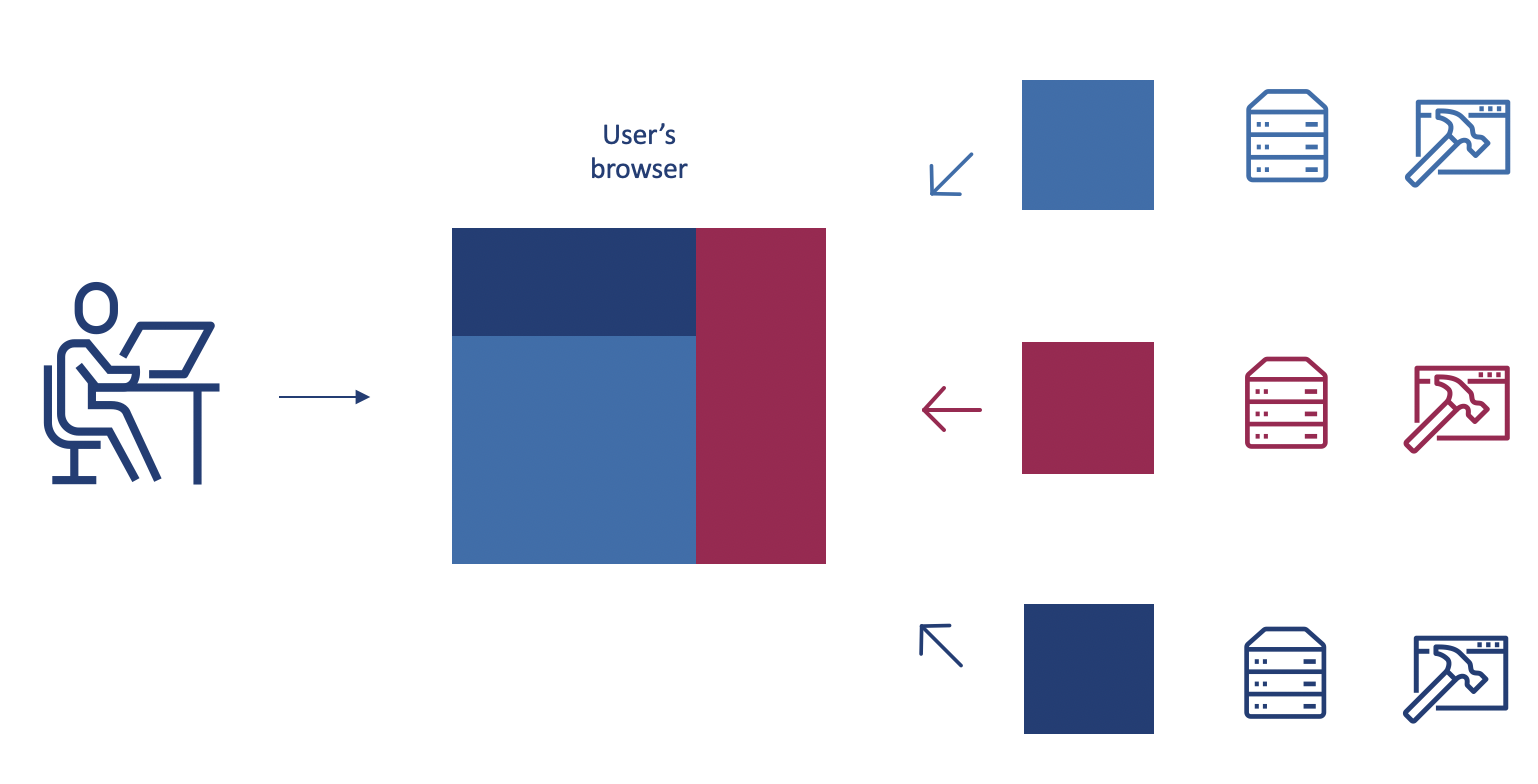

So far..

Source: https://micro-frontends.org/

Source: https://micro-frontends.org/

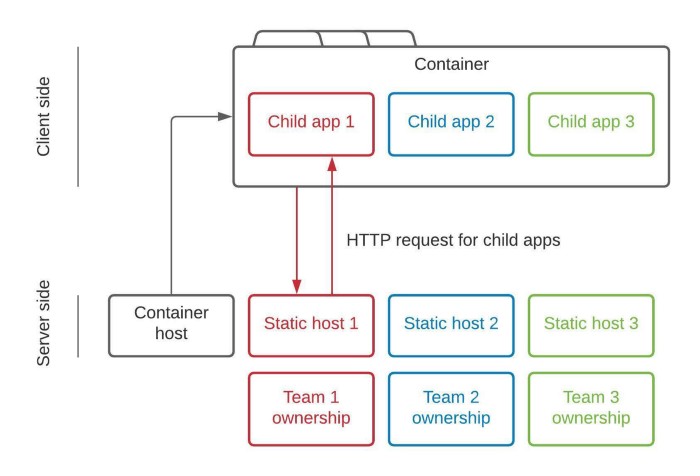

Going Forward

Source: https://micro-frontends.org/

Source: https://micro-frontends.org/

Beyond theory

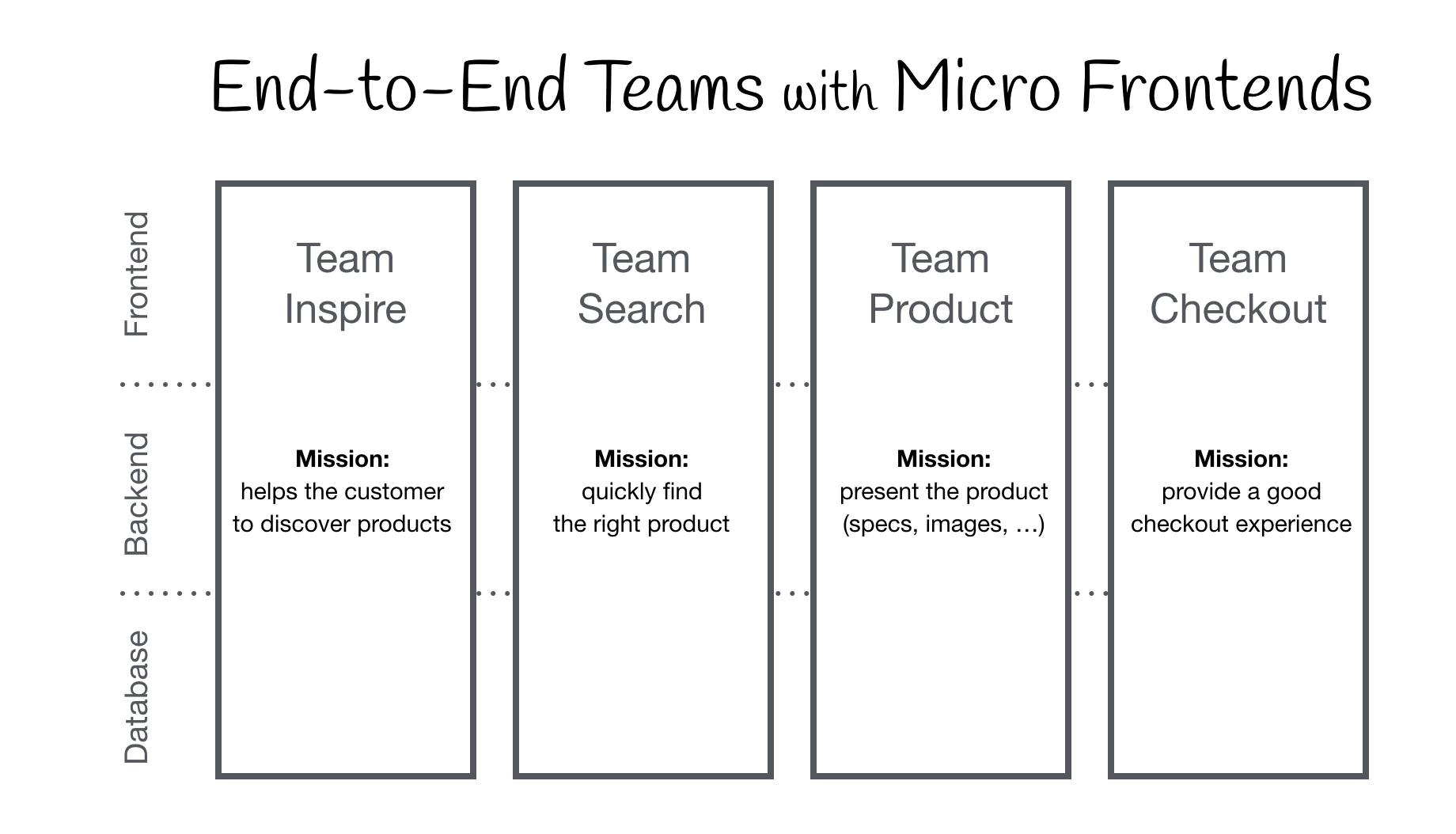

Consider an ecommerce website where customers can order stuff and have it delivered to them(take amazon.com for example). There is a surprising amount of detail involved if you want to do it in a scalable way: mf

- Customers should be able to browse and search for items on a landing page. The items should be searchable and filterable by a variety of criteria, such as price, category, or recommendation based on previous purchase.

- There is a cart component that handles the checkout process.

- Customers should be able to view their profile, order history, track delivery, and customize their payment options on their profile page.

Each page is complex enough that we could easily justify a dedicated team for each one, and each of those teams should be able to work on their page independently of the other teams. They should be able to develop, test, deploy, and maintain their code without having to worry about clashes or coordinating with other teams. Our customers, on the other hand, should continue to see a single, unified website.

Implementation methodologies

The two primary options that come to mind are build time integration and run time integration. Both options will necessitate a sensible division of your front end, whether by user journey, page, or collections of pages.

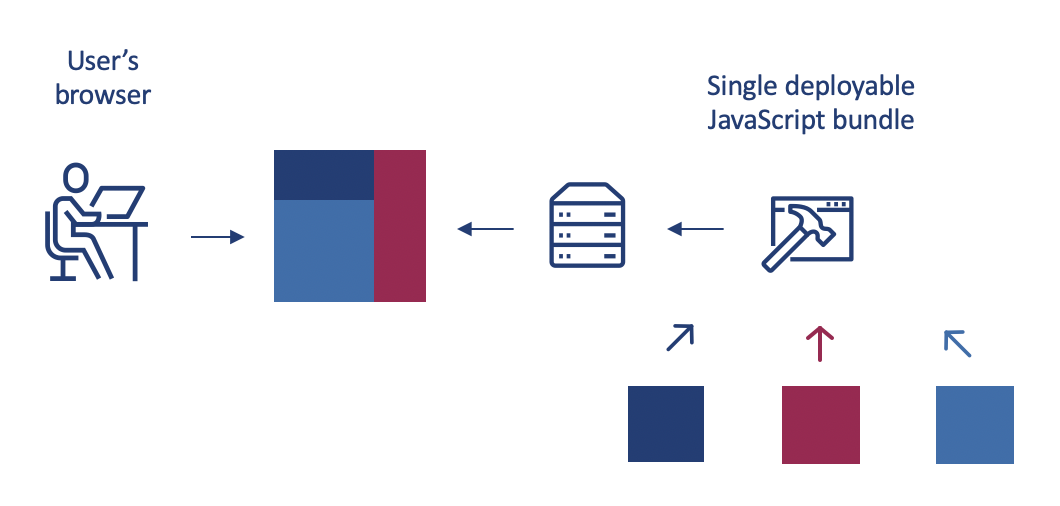

Build time integration

In this method you are exposing components as npm packages. You can then integrate them into a wrapper parent component, which will be the front end application that you deploy, using your preferred framework.The main advantage of this option is that it is extremely simple. I’ll go over how to do it in more detail below, but you probably already have a good idea of how to do it. One significant disadvantage of this method is that any change to a child component necessitates rebuilding and redeploying the parent. This method also makes it extremely appealing to marry the parent and child.

High level steps for build time integration:

- Create your child application (s)

- Export your router configuration file.

- Publish to npm (I recommend creating a CI pipeline that will automatically do version bumping and publishing to npm).

- In your parent application, include it as a node module.

- Include it in the parent application router file.

{

"name": "@ecommerce/container",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "A ecommerce web app",

"dependencies": {

"@ecommerce/browse-products": "^2.2.3",

"@ecommerce/cart": "^4.0.0",

"@ecommerce/user-profile": "^1.1.5"

}

}

Although this approach is marginally superior to the traditional monolithic approach, it defeats the purpose of loose coupling and dependency at the release stage. It is preferable to integrate micro-frontends at runtime. That is what we will look at next.

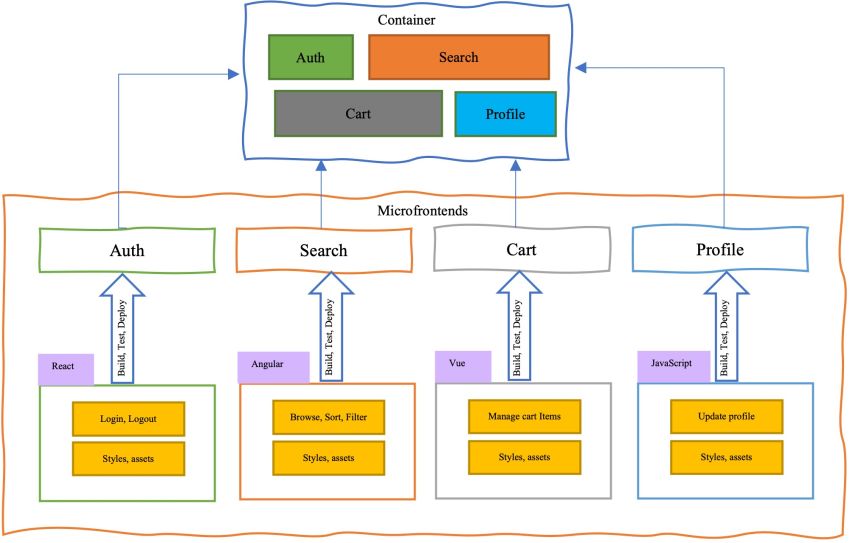

Run time integration

Each child app and the container app are deployed and served independently. At runtime, the container app will make HTTP requests to obtain the JavaScript required to render each child app as and when it is required. The main advantage is that each child component can be kept completely decoupled, to the point where you could use different frameworks for each child component if you wanted to. Each child can be developed and deployed independently of the parent container (after initial set up). This means that teams can have complete control and autonomy over how they do things without interfering with other teams.

Internals of run time integrations

Container - Base app

{

"name": "@ecommerce/container",

"description": "Entry point and container for ecommerce micro frontends app",

"scripts": {

"start": "PORT=3000 react-app-rewired start",

"build": "react-app-rewired build",

"test": "react-app-rewired test"

},

"dependencies": {

"react": "^16.4.0",

"react-dom": "^16.4.0",

"react-router-dom": "^4.2.2",

"react-scripts": "^2.1.8"

},

"devDependencies": {

"enzyme": "^3.3.0",

"enzyme-adapter-react-16": "^1.1.1",

"jest-enzyme": "^6.0.2",

"react-app-rewire-micro-frontends": "^0.0.1",

"react-app-rewired": "^2.1.1"

},

"config-overrides-path": "node_modules/react-app-rewire-micro-frontends"

}

App.js

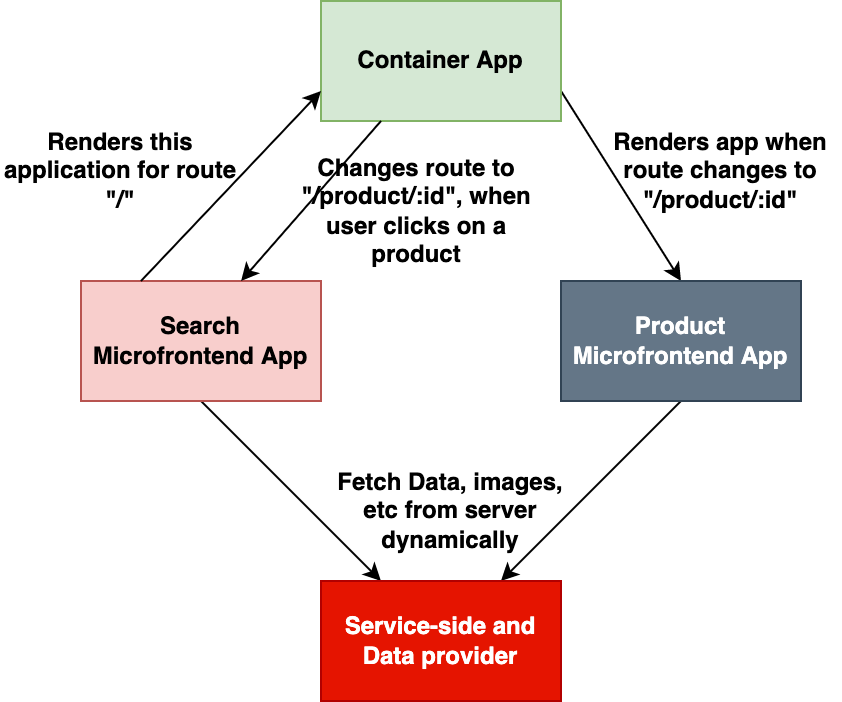

Examine App.js to see how we select and display a micro frontend. React Router is used to match the current URL against a predefined list of routes and render the corresponding component:

import React from 'react';

import { BrowserRouter, Switch, Route, Redirect } from 'react-router-dom';

import AppHeader from './AppHeader';

import MicroFrontend from './MicroFrontend';

import About from './About';

// Props injected via environment variables.

const {

REACT_APP_SEARCH_HOST: searchHost,

REACT_APP_PRODUCT_HOST: productHost,

} = process.env;

const Search = ({ history }) => (

<MicroFrontend history={history} host={searchHost} name="Search" />

);

const Product = ({ history }) => (

<MicroFrontend history={history} host={productHost} name="Product" />

);

const App = () => (

<BrowserRouter>

<React.Fragment>

<AppHeader />

<Switch>

<Route exact path="/" component={Browse} />

<Route exact path="/product/:id" component={Restaurant} />

<Route exact path="/about" render={About} />

</Switch>

</React.Fragment>

</BrowserRouter>

);

export default App;

We render a MicroFrontend component in both cases. Aside from the history object (which will be important later), we specify the application’s unique name as well as the host from which its bundle can be downloaded.

MicroFrontend.js

This is the base component that dynamically render a container element on the page with an ID unique to the micro frontend. We’ll tell our micro frontend to render itself here. The trigger for downloading and mounting the micro frontend is React’s componentDidMount:

import React from 'react';

class MicroFrontend extends React.Component {

componentDidMount() {

const { name, host, document } = this.props;

const scriptId = `micro-frontend-script-${name}`;

if (document.getElementById(scriptId)) {

this.renderMicroFrontend();

return;

}

fetch(`${host}/asset-manifest.json`)

.then(res => res.json())

.then(manifest => {

const script = document.createElement('script');

script.id = scriptId;

script.crossOrigin = '';

script.src = `${host}${manifest['main.js']}`;

script.onload = this.renderMicroFrontend;

document.head.appendChild(script);

});

}

componentWillUnmount() {

const { name, window } = this.props;

window[`unmount${name}`](`${name}-container`);

}

renderMicroFrontend = () => {

const { name, window, history } = this.props;

window[`render${name}`](`${name}-container`, history);

};

render() {

return <main id={`${this.props.name}-container`} />;

}

}

MicroFrontend.defaultProps = {

document,

window,

};

export default MicroFrontend;

Microfrontend - Search App

index.js - Entry point

import 'react-app-polyfill/ie11';

import React from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

import App from './App';

import { unregister } from './registerServiceWorker';

window.renderBrowse = (containerId, history) => {

ReactDOM.render(

<App history={history} />,

document.getElementById(containerId),

);

unregister();

};

window.unmountBrowse = containerId => {

ReactDOM.unmountComponentAtNode(document.getElementById(containerId));

};

From here on out, the micro frontends are mostly just plain old React apps. The ‘search’ application retrieves a list of products from the backend, provides “input” elements for searching and filtering the products, and renders React Router “Link” elements that direct the user to a specific product. At that point, we’d switch to the second, ‘order’ micro frontend, which renders a single products details.

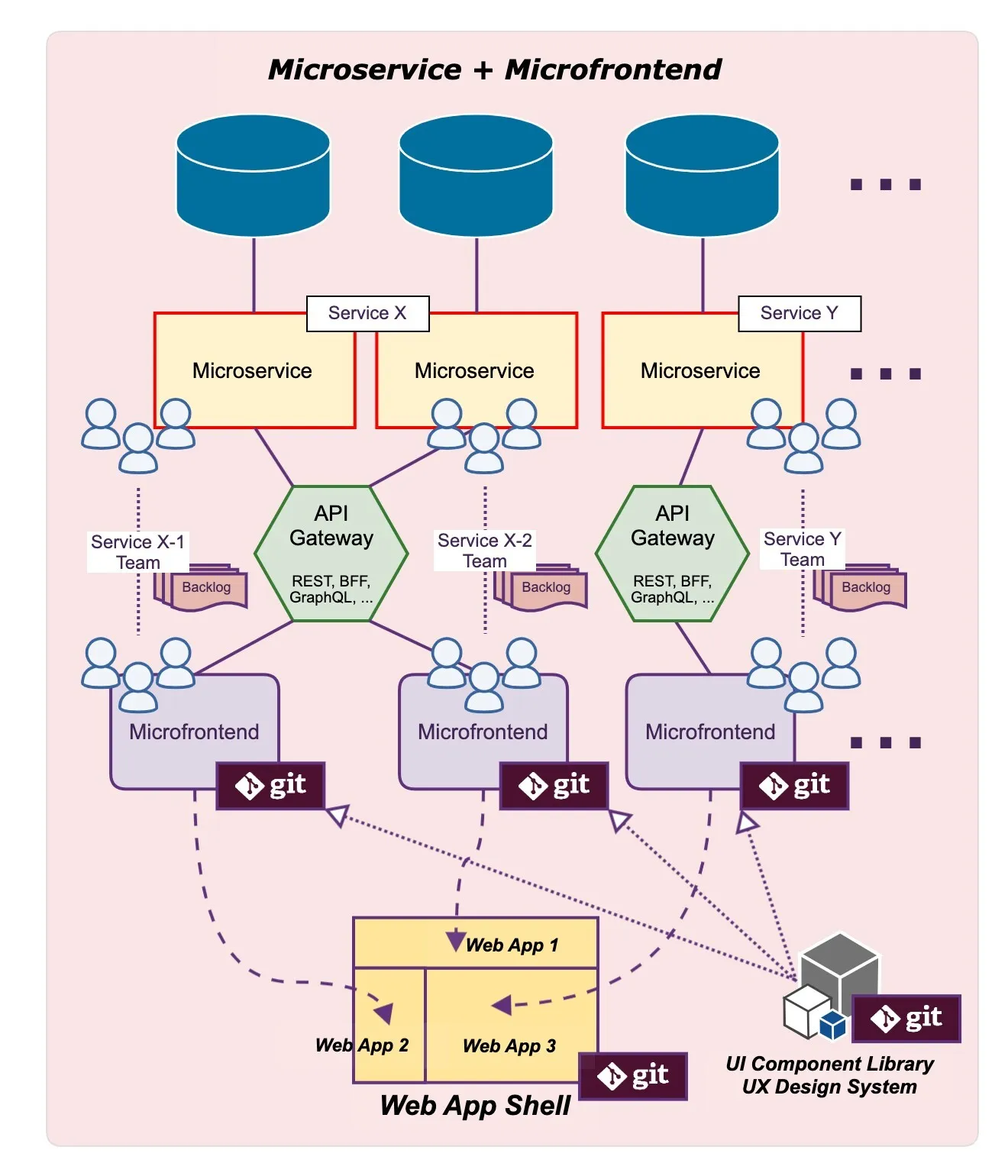

Match made in heaven - “Microfrontends & Microservices”

Domain-driven microservices and microfrontends go hand in hand. Communication between the two is contracted and routed over the network via APIs (such as REST or GraphQL) or via a backend for frontend (BFF) service that aggregates the data required for presentation from other upstream backend services.

Best practices for microfrontends

- Streamlined Operations and Governance model

- Automated integration and deployment model

- Stick to bounded context over making MF’s too granular

- Using Framework like single-spa.js, bit, module federation etc.

- Implement Lazy loading

- Shared libraries for styling and reusable components

Conclusion

If used correctly, micro frontends have a lot of potential. It is possible to build large, complex applications by allowing different teams to own different parts of the web application, but you should proceed with caution before using them. Preparation is essential for most patterns and techniques. As long as your teams communicate effectively and cross-cutting issues are addressed in a way that is understood by all parties involved, you should have no problems (at least none that aren’t easily solved).

Cheers and Happy Building 🤘